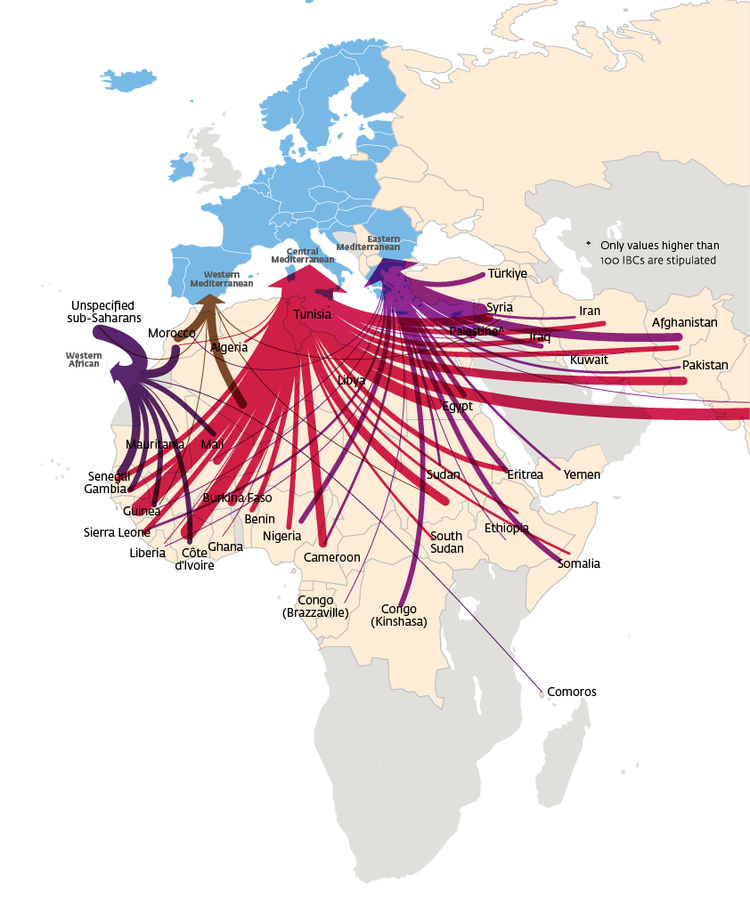

Every three months, the European Border and Coast Guard “Frontex”, releases a map documenting “detections of illegal border-crossing” along Central Mediterranean and Western Balkan migration routes into Europe (see Figure 1 as a visual example). These maps have been strongly criticised by migration scholars as “mythological” and “surrealist”, in their eurocentric and defensive portrayal of contemporary migrations towards Europe.

In order to become familiar with the dangers of map making and prepare for the creation of a critical, plural mapping of migrations into, out of and within Europe, the Lives in Motion education team has been analysing these Frontex maps with one of MIDI’s Geopolitics of Migrations students. All this to understand how such maps cement the eurocentric, white supremist power structures in migration narratives that we want to dismantle and counteract with #Livesinmotion. This article summarises our critical deconstruction of an exemplary Frontex map, examining how the map’s GRID, ARROWS and FRAME posit migration as a mono-directional, threatening phenomenon that Europe must defend itself from.

As you follow us through this step by step deconstruction, remember that maps are never inherently factual. On the contrary, maps always remove or simplify elements of a real life space and situation and visualise the world from the specific social, cultural and political perspective of their maker. In fact, as professor and cartographer Mark Monmonier says: “Maps always lie.” Since maps are always a symbolic and necessarily reductive interpretation of reality, they will always be informed by the choices, prejudices and intentions of their makers and they will always be visual representations of what philosopher John Searle calls “institutional facts”, “facts that require human institutions for their existence”. Thus the key to critically reading a map is to always ask: “Why has the maker decided to represent reality in this way?” “What are their intentions?”

THE GRID

The grid refers to the map’s demarcation of territory. It posits the European continent as the centre and focus of the world and displays land as a series of separate, delineated “compartments” which are defined by their national borders. The grid also makes people invisible: they are simply an anonymous and inseparable part of the territories and states in which they are compartmentalised.

THE ARROWS

The arrows on the Frontex map and their sharp, pointed heads depict “risks”, marking the act of migration as penetratively invasive and dangerous. As scholars Mitchell, Jones and Fluri remark: “they make the transit of people seeking shelter or work look as dangerous as incoming armed forces.” Furthermore, the swift lines sweeping up to the arrow’s swollen heads suggests quick, automatic and continuous journeys across the African continent towards Europe, as if migrations are taking place in an uninterrupted, unhindered flow.

THE FRAMING

The disproportionate size of the arrow’s head and its dominant position in relation to the rest of Europe (it’s made to look as big as the entire Iberian Peninsula, France, Germany and Britain), suggests the presence of uncontainable masses of people marching from Africa, the middle east and Asia to overwhelm Europe when in actual fact only 3.3% of the world’s population lives outside of their country of birth and undocumented migrants make up only 0.1-0.7% of EU’s total population. The contrast of colours in this frame: the dark red of the moving arrows typically suggesting abnormality, danger, warning, sexual promiscuity, anger and fear against the open, peaceful blue of Europe brings home the construction of undocumented migration as an intensive security threat to peace and order.

The grid, arrows and framing of the map transform the question of undocumented migration into a fast-moving, overwhelming source of menace for Europe, when in reality irregular migration is a numerically small phenomenon and paradoxically one of people’s only ways to exercise their right to asylum (Art. 18 Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union) and right to leave one’s country (Art. 12, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights): all the individuals of the world holding passports listed on the ‘negative’ Schengen list (135 out of 195 countries) have almost no chance of receiving a visa to enter the EU regularly on a humanitarian or work-related basis. It is this discrimination and construction of “paper borders”, a clear violation of Article I of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights”) that makes irregular passage to the EU into a necessary and inevitable mode of migration.

Sources

Columbro, D. (2021) Ti spiego il dato. Milano: Quinto Quarto

Earle, J. (1999) ‘The future of philosophy’, Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences, 354(1392),pp. 2069-2080;

Frontex. (2024) Migratory Routes. Available at : https://www.frontex.europa.eu/what-we-do/monitoring-and-risk-analysis/migratory-routes/migratory-routes/ (Accessed: date).

Van Houtum, H. and Bueno Lacy, R. (2020) ‘Ceci n’est pas la migration: The Surrealist migration map of Frontex’ in Mitchell, K., Jones, R. and Fluri, J L. (eds.) Handbook on Critical Geographies of Migration. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 153-169

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the granting authority. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.